Look at the picture to the left. What do you see?

Look at the picture to the left. What do you see?

In no time at all, most report a large face with deep set eyes and slight frown.

Actually, once seen, it’s difficult, if not impossible to unsee. Try it. Look away momentarily then back again.

Once set in motion, the process tends to take on a life of its own, with many other items coming into focus.

Do you see the ghostly hand? Skeletonized spine and rib cage? Other eyes and faces? A clown hat?

From an evolutionary perspective, the tendency to find patterns — be it in clouds, polished marble surfaces, burn marks on toast, or tea leaves in a cup — is easy to understand. For our earliest ancestors, seeing eyes in the underbrush, whether real or illusory, had obvious survival value. Whether or not the perceptions or predictions were accurate mattered less than the consequences of being wrong.

In short, we are hardwired to look for and find patterns. And, as researchers Foster and Kokko (2008) point out, “natural selection … favour[s] strategies that make many incorrect causal associations in order to establish those that are essential for survival …” (p. 36).

As proof of the tendency to draw incorrect causal associations, one need only look at the field’s most popular beliefs and practices, many of which, the evidence shows, have little or no relationship to outcome. These include:

- Training in or use of evidence-based treatment approaches;

- Participation in clinical supervision;

- Attending continuing education workshops;

- Professional degree, licensure, or amount of clinical experience;

Alas, all of the above, and more, are mere “faces in the clouds” — compelling to be sure, but more accurately seen as indicators of our desire to improve than reliable pathways to better results. They are not.

So, what, if anything, can we do to improve our effectiveness?

According to researchers Stiles and Horvath (2017), “Certain therapists are more effective than others … because [they are] appropriately responsive … providing each client with a different, individually tailored treatment” (p. 71).

Sounds good, right? The recommendation that one should “fit the therapy to the person” is as old as the profession. The challenge, of course, is knowing when to respond as well as whether any of the myriad “in-the-moment” adjustments we make in a given therapy hour actually help.

That is until now.

Consider a new study involving 100’s real world therapists and more than 10,000 of their clients (Brown and Cazauvielh, 2019). Intriguingly, the researchers found, therapists who were more “engaged” in formally seeking and utilizing feedback from their clients regarding progress and quality of care — as measured by the frequency with which they logged in to a computerized outcome management system to check their results — were significantly more effective.

Consider a new study involving 100’s real world therapists and more than 10,000 of their clients (Brown and Cazauvielh, 2019). Intriguingly, the researchers found, therapists who were more “engaged” in formally seeking and utilizing feedback from their clients regarding progress and quality of care — as measured by the frequency with which they logged in to a computerized outcome management system to check their results — were significantly more effective.

How much, you ask?

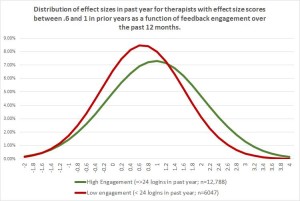

Look at the graph above. With an effect size difference of .4 σ, the feedback-informed practitioners (green curve) were on average more effective than 70% of their less engaged, less responsive peers (the red).

Such findings confirm and extend results from another study I blogged about back in May documenting that feedback-informed treatment, or FIT, led to significant improvements in the quality and strength of the therapeutic alliance.

Why some choose to actively utilize feedback to inform and improve the quality and outcome of care, while others dutifully administer measurement scales but ignore the results is currently unknown — that is, scientifically. Could it really be that mysterious, however? Many of us have exercise equipment stuffed into closets bought in the moment but never used. In time, I suspect research will eventually point to the same factors responsible for implementation failures in other areas of life, both personal and professional (e.g., habit, lack of support, contextual barriers, etc.).

Until then, one thing we know helps is community. Having like-minded to interact with and share experiences makes a difference when it comes to staying on track. The International Center for Clinical Excellence is a free, social network of practitioners working in diverse settings around the world. Every day, they meet to address questions and provide support to one another in their efforts to implement feedback-informed treatment. Click on the link to connect today.

Still wanting more? Listen to my interview with Gay Barfield, Ph.D., a colleague of Carl Rogers, with whom she co-directed the Carl Rogers Institute for Peace –an organization that applied person-centered principles to real and potential international crisis situations, and for which Dr. Rogers was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1987. I know her words and being will inspire you to seek and use client feedback on a more regular basis…

4 responses to “Responsiveness is “Job One” in Becoming a More Effective Therapist”

Great post, humans are an pattern-discovering species. In fact, Rens Bod, president of the International Society for the History of Humanities has written a fascinating history on the subject: http://www.letterenfonds.nl/en/book/1231/a-world-of-patterns

As therapists especially, we have to realize that patterns are not reality. The writings of the late Steve de Shazer come to mind. There is always a vast space of unknown and yet unrecognized patterns, when interacting with our clients. Once we realize that the chosen pattern isn’t working, we need to look for better fitting patterns.

This made me wonder about the space between myself and my client this afternoon; so many treatment needs but underlying it all was a far from solid foundation of love and security. How can I fill that space with compassion and help her receive it? I couldn’t think about trying to problem solve or steer her in any treatment direction without hearing her and feeling connection first. It can take a long time, and whenever I deviate from this belief, it sets back the growth of the relationship. I just don’t think I know how to write this in the Individualized Service Plan with the proper emphasis. It’s more than rapport and may be too subjective for the payor. In practice, of course, we write what is objective and measurable but it seems awful not to have words for creating a sacred space with each person.

Most, if not all, of the debates in our beloved profession may be attributed to those

who believe that each human being has a unique psychological history, with correspondingly unique problematic psychological functioning, and those who hold that concepts have more validity in explaining such behavior as they are only concerned with what client’s problems supposedly have in common.

Conclusion: The best therapists are the ones who view each client as having their own unique psychological experience AND support that experiencing as best as they are able, or they are as “responsive” as they can be.

This thinking helps to explains why FIT is as effective as it is, and also why some regard it as a bona fide method of treatment. FIT allows the client to “speak” to the therapist! For the CBT folks and their ilk that’s an absolutely absurd idea! Therapists who see each client as having a unique history are poised to take the next step in becoming decidedly more effective.

My concept of therapeutic catharsis is offered as a fundamental re-conceptualization of how catharsis as been traditionally understood. It offers a criterion for when an emotional release is therapeutic and when it is not. That criterion is the unforced/unprovoked activation of the client’s emotional experiencing, which occurs coincident with the client having received sufficient support for whatever he or she has been experiencing. This concept also explains why the fear of re-traumatization is an understandable though serious misconception about the client’s emotional experiencing.

Besides PsycINFO, two of my articles are on ResearchGate. Search: Jeffrey Von Glahn.

Touching video – and convincing blog posting. Wonderful reminder of a time when psychotherapy was often a kinder and gentler practice and an inspirational “nudge” to reconsider our focus in clinical practice. Love that you’re offering tools to aid in integration of the human factors with a technology to help practice be more data-driven AND humanistic. Thank you, Drs. Scott and Gay!